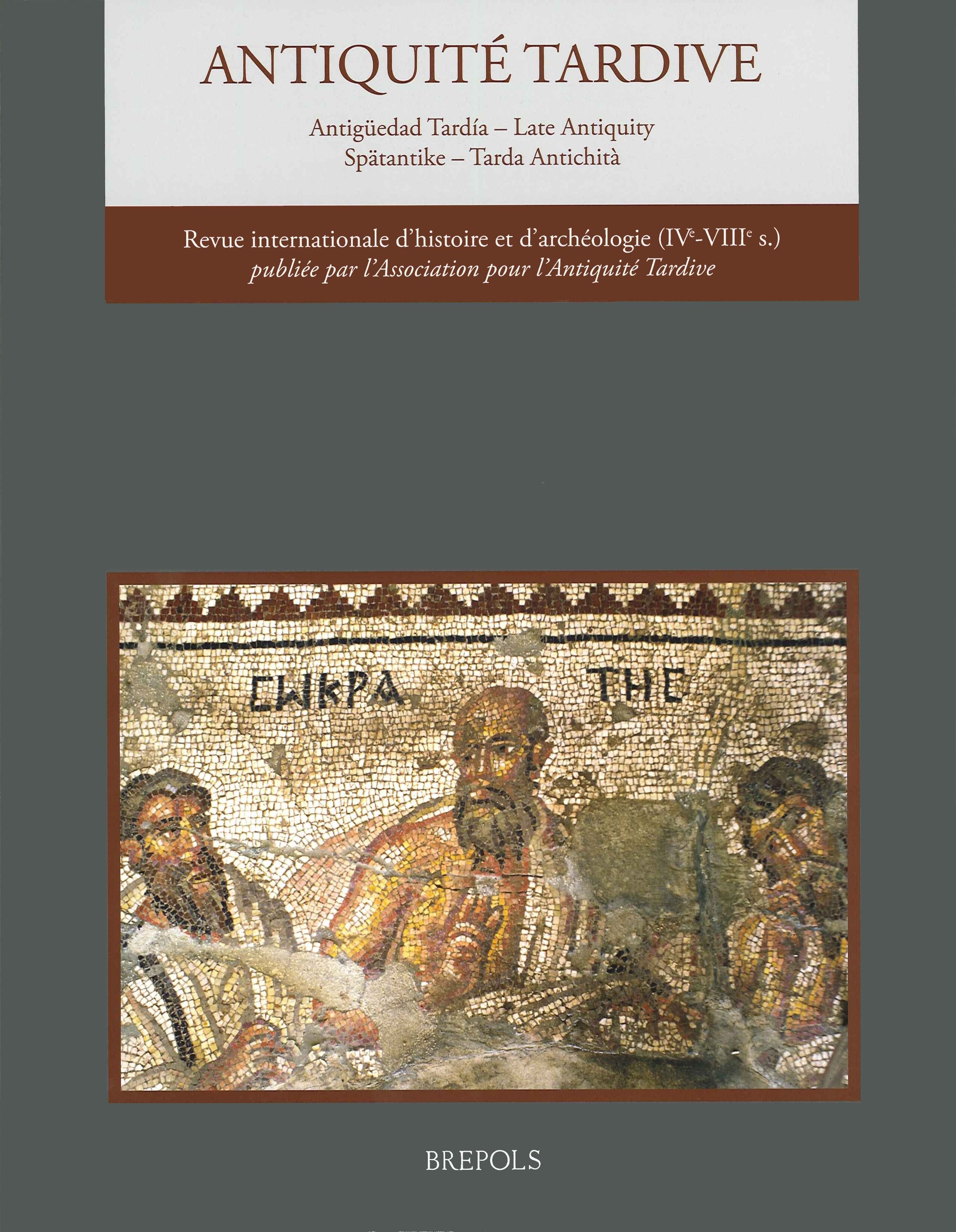

Antiquité Tardive - Late Antiquity - Spätantike - Tarda Antichità

Revue Internationale d'Histoire et d'Archéologie (IVe-VIIIe siècle)

Volume 28, Issue 1, 2021

-

-

Front Matter (“Principales abréviations”, “Table des matières”, “Éditorial”)

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Front Matter (“Principales abréviations”, “Table des matières”, “Éditorial”) show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Front Matter (“Principales abréviations”, “Table des matières”, “Éditorial”)

-

- 1. L’eau sous contrôle : administrer et gérer les ressources

-

-

-

Action impériale et aqueducs urbains au ive et au début du ve siècle

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Action impériale et aqueducs urbains au ive et au début du ve siècle show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Action impériale et aqueducs urbains au ive et au début du ve siècleBy: Marguerite RoninAbstractRoman authorities were very well aware of the vulnerability of aqueducts. The infrastructures regarding ageing, clogging up of pipes or damage caused by human activity along the conduits are frequently mentioned in ancient texts. Needs for running water in 4th century cities of the Empire were high, especially in the new capital of Constantinople, which began to grow considerably at that period and where an extensive network of long-distance water supply was developed. Imperial constitutions reveal that, although the missions of urban water authorities remained unchanged with respect to the previous centuries, their means and resources were redistributed to meet new priorities.

-

-

-

-

La gestione finanziaria dell’acqua in ambito urbano tra IV e V secolo

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:La gestione finanziaria dell’acqua in ambito urbano tra IV e V secolo show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: La gestione finanziaria dell’acqua in ambito urbano tra IV e V secoloBy: Raffaella BiundoAbstractRegarding the administration of water and especially its financial management in Late Antiquity, the documentation is rather sporadic. Nonetheless, the analysis of the sources, especially the legal ones, allow us to perceive the existence of a well-organized administration system although some details escape us. This administration had its own headquarters (statio), where the registers for the distribution of water were kept. It furthermore managed, through a specific financial department (ratio), all accounts related to water and a “chest” (arca) concerning the expenses and incomes of different nature. Although, this was only one of many rationes of the fiscus and probably also administered quite similarly as the various accounts concerning the food supply system in Rome and Constantinople, accounts often interconnected to each other and, from the 4th century onwards, fell under the supervision of the urban prefects. Besides, the fact that it is mainly within the constitutions of emperors that the protection of water and its uses were addressed, one can assume that there was a persistently present central authority, which tried, by special laws and interdictions, to preserve and guarantee the water supply to citizens. The imperial edicts do therefore reflect that the guarantee of water supply was an act of benevolence on the part of Emperors, towards the citizens. However, it should be emphasized that this was also true with regards to other essential aspects of civic life: guaranteed food supply, urban splendour, public order, facilities and welfare.

-

-

-

Soliditas aquaeductus ... servetur. Controllo e amministrazione degli acquedotti nell’Italia ostrogota

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Soliditas aquaeductus ... servetur. Controllo e amministrazione degli acquedotti nell’Italia ostrogota show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Soliditas aquaeductus ... servetur. Controllo e amministrazione degli acquedotti nell’Italia ostrogotaBy: Yuri A. MaranoAbstractWritten and archaeological evidence from Ostrogothic Italy offers the opportunity to investigate how a late antique society coped with hydraulic problems. Although stretching across a few decades (from the establishment of Theoderic’s power over Italy in AD 493 and the end of the Gothic war in AD 555), the Ostrogothic period is marked by social, economic, political and cultural transformations which affected the management of water. Ostrogothic authorities held control over aqueducts and the water supply following earlier administrative and legal tradition. Though there is evidence for private misappropriation of part of public aqueducts’ water, the main function of aqueducts - to make ample supplies of water available to entire communities - was generally achieved. At the same time, it is undeniable that they had to cope with irreversible trends, whose impact was magnified by major historical events such as the Gothic war.

-

- 2. L’eau conduite et l’eau rejetée : techniques et systèmes hydrauliques

-

-

-

Les aqueducs de Gaule romaine de l’Antiquité tardive, entre construction, restauration et abandon

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Les aqueducs de Gaule romaine de l’Antiquité tardive, entre construction, restauration et abandon show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Les aqueducs de Gaule romaine de l’Antiquité tardive, entre construction, restauration et abandonAuthors: Laëtitia Borau and Stéphane AlixAbstractFew studies are dedicated to the aqueducts of Roman Gaul during Late Antiquity. The objective here is to explore the situation of the water supply network, mainly those of capitals of cities, from the transition phase of the 3rd century, and based on the examination of representative sites such as Lyon, Bordeaux, Périgueux, Reims, Narbonne or Nîmes. Several situations are thus intended: the abandonment of aqueducts from Late Antiquity, the keeping of these canalisations through regular maintenance, occasional restorations or partial reconstructions, or even new constructions. The study of the insertion of these water networks in the urban grid as well as their relationship with the related structures such as water pipes, fountains or thermal baths provides essential information to understand the continuity of the aqueducts. Far from being exhaustive, this research lays the basis for an analysis that deserves to be much more in-depth, as evidenced by the diversity and richness of the presented case studies. Contrary to a generally widespread idea, it shows that water supply networks seem to have been maintained, in different circumstances from one city to another, at least during part of Late Antiquity in the different provinces of Roman Gaul.

-

-

-

-

Recherches interdisciplinaires sur l’alimentation et l’évacuation des eaux du palais de Dioclétien à Split

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Recherches interdisciplinaires sur l’alimentation et l’évacuation des eaux du palais de Dioclétien à Split show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Recherches interdisciplinaires sur l’alimentation et l’évacuation des eaux du palais de Dioclétien à SplitAuthors: Katja Marasović and Jure MargetaAbstractFrom 2014 until 2018, at the Faculty of Civil Engineering, Architecture and Geodesy of the University of Split, the project “Roman Water Systems of Salona and the Diocletian’s Palace and their Impact on the Sustainability of the Urban Environment” was carried out by an interdisciplinary team of archaeologists, architects and civil engineers. All archival sources, published papers and unpublished reports of archaeological excavations were gathered and analysed, and led to new conclusions on the Roman urban water systems of Salona and the Palace. This paper presents some of these very recent results regarding the water supply and sewage system of Diocletians Palace in Split. Notably, the aqueduct leading to the Diocletian’s Palace has been well preserved (since at the end of the 19th century it was reconstructed, with more than half of its route still used for the water supply of the city of Split). Within the Palace itself, a great part of the sewage system was equally well preserved and allows that its original structure and features may be reconstructed. Both, the aqueduct as well as the sewage system give an excellent insight in the planning and execution of Roman urban water systems. Surprisingly, its planned approach, parameters, conception as well as specific solutions and details are much in accordance with the nowadays standard practice of water engineering, that has not changed siginificantly.

-

-

-

El ciclo del agua en Barcino en la antigüedad tardía

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:El ciclo del agua en Barcino en la antigüedad tardía show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: El ciclo del agua en Barcino en la antigüedad tardíaAbstractSince its foundation Barcino has had a complex water supply system, that goes from the collection of water from a source near the river Besós, to the distribution within the city, where one also finds structures regarding the management of wastewater. This water cycle, planned in the time of Octavius Augustus, has survived and evolved throughout the imperial period, having undergone significant renovations and design in Late Antiquity, but which have not affect the supply of drinking water that reached the city, as throughout the 4th century several private balnea were built, and later on the bath in the bishop’s palace.

-

-

-

Wasser im spätantiken Trier – neue Einblicke

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Wasser im spätantiken Trier – neue Einblicke show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Wasser im spätantiken Trier – neue EinblickeBy: Florian TanzAbstractAlready in the first two centuries AD, two aqueducts supplied Augusta Treverorum, and especially the huge Barbarathermen. In the early 4th century when Trier became an imperial residence, a large-scale building program was initiated, which concurrently affected the city’s water distribution system. The connection of the main sewer of the Kaiserthermen (which were never finished) with the older sewer canal in street no. 8 was discovered in 2010. In keeping with most of the other late antique canals, the walls were constructed of brick, the production of some can be traced to late antique brick factories. Most of the “new” sewer canals were found in the area of the imperial palace, for example the canals at Schützenstraße, where the Roman circus is presumed to have been located. In the second half of the 4th century, a new aqueduct bridge was built along the present-day Olewiger Straße, which probably constituted the “new” ending of the older Ruwer aqueduct. In a reused building near the forum, a new bath building (the Viehmartthermen) was installed. The main sewer canal of these baths was lined with waterproof mortar, as was standard for water supply canals. Further evidence for water constructions in late antique Trier include more than a dozen small bathhouses as well as a splendid fountain found during excavations in the 19th century on the other side of the Mosel River. Sumptuous water display came to an end in the 5th century when the Romans no longer occupied the region.

-

-

-

‘Still waters run deep’: cisterns and the hydraulic infrastructure of Constantinople and Alexandria

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:‘Still waters run deep’: cisterns and the hydraulic infrastructure of Constantinople and Alexandria show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: ‘Still waters run deep’: cisterns and the hydraulic infrastructure of Constantinople and AlexandriaBy: James CrowAbstractLes deux grandes villes de Méditerranée orientale, Constantinople et Alexandrie, sont connues pour le nombre important de citernes antiques et médiévales qui y sont encore conservées. À partir de résultats de projets de recherche récents menés dans ces deux villes, cet article a pour objectif d’offrir une meilleure connaissance des ressources souterraines et de montrer comment celles-ci contribuent à éclairer l’histoire urbaine de l’Antiquité tardive et des périodes postérieures. Le caractère unique des hyponomoi alexandrins est décrit dans le contexte hydrogéologique de la ville. Des études récentes ont révélé l’importance des changements de la qualité de l’eau sur le long terme et les réponses apportées par de nouvelles citernes, plus grandes, entre le ve et le viiie siècle. Les nombreuses citernes connues par d’anciennes descriptions d’Alexandrie comme par les recherches actuelles sont considérées comme remontant au moins au xe siècle. Pour Constantinople, les recherches récentes ont montré que 209 citernes sont connues dans la péninsule historique : leur répartition est analysée et la citerne du monastère de Stoudios choisie comme nouveau cas d’étude puisqu’elle est structurellement antérieure à la basilique datée de 463. L’aménagement de cette citerne et d’autres de la même époque présente une forme innovante que l’on retrouve dans toute la ville. La comparaison avec les études récentes de Salamine à Chypre et Resafa en Syrie permet d’appréhender les processus de construction dans le contexte de nos connaissances relatives aux premières citernes romaines d’Afrique du Nord. Les études géochimiques des conduits d’aqueducs offrent un nouveau regard sur la qualité de l’eau des aménagements thraces, étudiée en rapport avec la fonction des grandes citernes ouvertes. La conclusion analyse les divers usages des citernes dans chacune des deux villes.

-

-

-

Byzantine water towers in the East: Palmyra and Apameia

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Byzantine water towers in the East: Palmyra and Apameia show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Byzantine water towers in the East: Palmyra and ApameiaBy: H. Paul KessenerAbstractLes châteaux d’eau sont une des caractéristiques du système romain de distribution d’eau à Pompéi. Des réservoirs d’eau posés sur des tours de 6 m de hauteur étaient interconnectés par des conduits en plomb d’eau sous pression. À partir de ces réservoirs, ces conduits menaient vers les fontaines publiques, les bains et les maisons privées. Dans l’Istanbul ottomane, un système de distribution d’eau avec châteaux d’eau, appelés suterazi, était, comme à Pompéi, le système standardisé. Un système semblable existait à Paris, depuis au moins la Renaissance jusqu’à la fin du xixe siècle, et même à Palerme en Sicile jusque dans les années 1960. Pourtant, à Istanbul, aucun château d’eau de l’époque byzantine n’est signalé. Pour comprendre si ces derniers étaient courants à l’époque byzantine et avaient existé à Constantinople avant la conquête de 1453, l’étude se concentre sur les systèmes de distribution d’eau de Palmyre et d’Apamée, deux cités byzantines conquises par les Arabes au viie siècle.

-

- 3. L’eau des bains et des latrines : pratiques corporelles et sociales

-

-

-

Cogitatio, inventio e natura loci. I progetti dei balnea in età tardoantica nel paesaggio urbano di Roma e Ostia

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Cogitatio, inventio e natura loci. I progetti dei balnea in età tardoantica nel paesaggio urbano di Roma e Ostia show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Cogitatio, inventio e natura loci. I progetti dei balnea in età tardoantica nel paesaggio urbano di Roma e OstiaAbstractFrom the Cataloghi Regionari we know that at the beginning of the 4th century, in addition to the public thermae, there were hundreds of balnea in the city of Rome. Privately owned baths, identifiable by dimensions, accessibility and other indicators, were either used privately by the élite in their domus, or open to the public in the case of so the called balnea meritoria, or even used by collegia. During recent investigations, more than forty ‘private’ baths of Rome and Ostia built or still in use in Late Antiquity (late 3rd-6th century) had been studied in detail and classified by their location, date, dimensions, accessibility and buildings techniques as well as ornamental features (Giovanetti 2015-2016). Stemming from published contexts, as well as archival research, surveys and written sources, this paper focuses on the design of late antique balnea found in both cities. Architectural koinè and the common language that shaped and characterized the design of ‘private’ baths in the 4th century will be highlighted. In addition to the recycling of materials and the re-use of buildings, in fact repeated elements like the sizes of rooms, design of bathtubs or entire bath plans are an indication that they were constructed by the same workers or that building plans must have circulated. From the 5th century onwards, thermae and balnea are increasingly abandoned. Although a few smaller new baths continued to be built in ecclesiastical spaces, they are characterised by different features and built in an altered socio-economic frame.

-

-

-

-

Shared water. Bathing culture and friendship in Late Antiquity

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Shared water. Bathing culture and friendship in Late Antiquity show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Shared water. Bathing culture and friendship in Late AntiquityBy: Seraina RuprechtAbstractDe nombreux liens d’amitié rapprochaient les élites de l’Antiquité tardive. Dans la mesure où l’importance d’un homme était fortement reflétée par ses amis, il était crucial que ces derniers soient bien connus parmi ses pairs. De nombreuses formes d’interaction sociale dans la vie quotidienne de ces élites rendaient ces liens visibles. La manière dont chacun se saluait dans la rue, les personnes à qui elles rendaient visite le plus fréquemment et qu’elles invitaient à dîner étaient des indicateurs clairs de la nature de leurs relations. Alors que la recherche s’est attachée jusqu’à présent à l’analyse de ces formes de communication à l’époque impériale, les changements qui ont pu intervenir durant l’Antiquité tardive n’ont pas encore été étudiés en détail. En outre, un lieu de rencontre particulier n’a jamais été analysé sous cet angle : les bains. Dans cet article, je montrerai que le bain peut être considéré comme l’une des pratiques sociales qui constituaient et manifestaient les amitiés. Pour cela, j’examinerai les témoignages écrits de Libanius, Jean Chrysostome et des historiens ecclésiastiques grecs. Cette étude compare les pratiques et les significations du bain traditionnel et chrétien, en se concentrant sur la partie orientale de l’Empire romain à partir du ive siècle.

-

-

-

Washing the body, cleaning the soul. Baths and bathing habits in a Christianising society

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Washing the body, cleaning the soul. Baths and bathing habits in a Christianising society show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Washing the body, cleaning the soul. Baths and bathing habits in a Christianising societyBy: Sadi MaréchalAbstractMalgré les profondes transformations du monde antique liées au développement du christianisme, les sources littéraires, épigraphiques et archéologiques montrent que les bains et les coutumes balnéaires ne changèrent guère. D’une part, cette continuité s’explique par une persistance des idées sur le fonctionnement du corps humain : l’équilibre des différentes humeurs assuraient une bonne santé. Le bain servait à entretenir cet équilibre ou à le rétablir en cas de maladie. D’autre part, les bains demeuraient des lieux de rencontre importants, qui continuaient à être construits, maintenus et restaurés par les personnes au pouvoir. L’Église même s’engageait parfois pour offrir des bains aux croyants. Les critiques les plus acérées, comme le bain prolongé, les bains mixtes ou l’étalage de sa richesse aux bains, ne se limitaient pas aux auteurs chrétiens. En refusant de participer à la vie sociale et de répondre aux attentes de propreté, l’abstention de bain n’était autre qu’un acte de rébellion contre la société. Seuls les chrétiens les plus rigoristes, comme les moines, les ascètes ou les vierges, s’abstenaient du plaisir du bain et ne fréquentaient le lieu que pour leur santé.

-

-

-

A farewell to foricae: changing attitudes to public latrines in the late antique Near East and Asia Minor

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:A farewell to foricae: changing attitudes to public latrines in the late antique Near East and Asia Minor show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: A farewell to foricae: changing attitudes to public latrines in the late antique Near East and Asia MinorBy: Louise BlankeAbstractCet article examine le développement des latrines publiques à plusieurs sièges (foricae) dans les villes tardives du Proche-Orient et de l’Asie mineure. Il résume la conception et l’utilisation des latrines publiques collectives dans le monde romain et analyse leur distribution dans les villes italiennes qui ont fait l’objet de fouilles approfondies. À partir de quatre études de cas archéologiques de Méditerranée orientale, l’article examine comment des villes de différentes régions ont adapté les latrines à leur environnement bâti. Cette partie est suivie d’un aperçu des changements survenus dans la pratique de l’utilisation des latrines à la suite de la conquête arabe. L’article se termine par une discussion sur la diversité régionale de l’utilisation des latrines dans l’Antiquité tardive et sur l’impact des sensibilités religieuses quant à leur integration

-

-

-

Sui diversi usi dell’acqua nelle enciclopedie mediche della Tarda Antichità: Da Oribasio di Pergamo a Paolo Egineta

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Sui diversi usi dell’acqua nelle enciclopedie mediche della Tarda Antichità: Da Oribasio di Pergamo a Paolo Egineta show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Sui diversi usi dell’acqua nelle enciclopedie mediche della Tarda Antichità: Da Oribasio di Pergamo a Paolo EginetaBy: Irene CalàAbstractThis paper will focus on the different uses of water in the medical works of Late Antiquity by examining medical treatises of Oribasius of Pergamon (4th century), Aetius of Amida (6th century) and Paul of Aegina (7th century). Initially texts regarding the therapeutic properties of the water such as healing bath or healing beverage, are examined and commented in detail; especially in relation to the medical tradition in general, and in particular to the Pneumatic School. Additionally, the paper will examine in depth and detail a long passage ascribed to Rufus of Ephesus, as the geographical information mentioned by the author can be compared with that referred in other ancient authors, e.g. Pliny the Elder. Furthermore, it will dedicate a section to the analysis of the so called “Albula waters”, which was a treatment in Antiquity recommended to cure elephantiasis. In the last selection, some unpublished recipes to use in the bath will be discussed.

-

- 4. L’eau mise en scène : mémoire et prestige

-

-

-

Fountains, experience, and meaning in late antique Corinth

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Fountains, experience, and meaning in late antique Corinth show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Fountains, experience, and meaning in late antique CorinthBy: Dylan K. RogersAbstractAu cours de ces dernières décennies, les travaux sur la Grèce de l’Antiquité tardive sont passés d’une image d’effondrement et de déclin à celle d’une vitalité retrouvée, en particulier sur le site de Corinthe. Les origines anciennes et la période romaine florissante qu’a connue Corinthe ont tissé un passé mythico-historique unique qui a nourri son identité collective. Au cours des ive-vie siècles, la ville a continué de prospérer et de se développer, en particulier en ce qui concerne l’entretien et la consommation d’eau. Cet article s’appuie sur le cas des fontaines tardives de Corinthe pour souligner le sentiment partagé d’une culture de l’eau qui était attachée à la mémoire, à l’identité, aux sens et aux expériences sociales au sein même de la ville et de sa périphérie. Après une présentation générale des fontaines de Grèce et d’Asie Mineure de l’Antiquité tardive, et une introduction sur la Grèce tardo-antique et sur Corinthe, sont analysés en détail la fontaine Pirène et celles adjacentes sur la zone du forum, de même qu’un grand nymphée de la villa de Lechaion. La mise en scène et la consommation de l’eau dans et autour de ces structures montrent la nature dynamique de la Corinthe tardive, au sein d’un vaste réseau de centres urbains de Méditerranée orientale tout aussi prospères à cette période.

-

-

-

-

Water and wealth: Aquatic display in a late antique neighbourhood at Ostia (IV, 3-4)

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Water and wealth: Aquatic display in a late antique neighbourhood at Ostia (IV, 3-4) show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Water and wealth: Aquatic display in a late antique neighbourhood at Ostia (IV, 3-4)By: Ginny WheelerAbstractL’abondance et la mise en scène de l’eau sont depuis longtemps considérées comme des indices de la vitalité urbaine et du prestige social dans le monde romain. À Ostie, les vestiges de plus de 200 fontaines et nymphées ont été répertoriés ; cependant, le rôle de l’eau en tant que bien de luxe dans le développement urbain à une échelle restreinte reste à explorer. Cet article se concentre sur un quartier en particulier - les deux groupes de maisons au sud du forum civil d’Ostie -dans lequel huit fontaines ont été construites de la fin du iiie au début du ve siècle. La motivation probable de leur aménagement est d’abord identifiée, puis les formes et le positionnement des fontaines dans la reconfiguration et l’ornementation des espaces domestiques individuels sont étudiés. La centralité et la splendeur caractéristiques de ces fontaines confirment que l’eau en tant que moyen de décoration était très appréciée et méritait un investissement substantiel. Cet article examine les rôles urbains, architecturaux et esthétiques des jeux d’eau au niveau du quartier, tout en contribuant à des recherches récentes mettant l’accent sur la vitalité continue du centre-ville d’Ostie dans l’Antiquité tardive.

-

- Varia

-

-

-

Une image peut en cacher une autre : le décor absidal du Vieux-Saint-Pierre à Rome

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Une image peut en cacher une autre : le décor absidal du Vieux-Saint-Pierre à Rome show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Une image peut en cacher une autre : le décor absidal du Vieux-Saint-Pierre à RomeBy: Yves ChristeAbstractDoes the mosaic in the apse of Old Saint Peter’s in Rome, around 360, really illustrate a “Traditio legis”? This emblematic image of the Roman funerary art from 360-400 is no longer relevant since 400, and disappear almost completely around 450. There only remain a few evidence of it, always associated with the giving of the Book to Peter. The absence of this particular iconographical theme after 400 seems inconsistent with the prestige that it would have acquired in Old Saint Peter’s. Single example of the real “Traditio legis” in its Paleochristian formula, the apse’s decoration of San Silvestro of Tivoli add to this iconographical theme the one of the apse program of the church of Santi Cosma e Damiano, which has a rich and varied medieval prosperity, in contrast to the Old Saint Peter’s. I would hence conclude that it is the decoration of the Forum church that truly transcribes the one of the Martyrium of Saint Peter in its final iconographical formulation.

-

-

-

-

Témoignages épigraphiques sur le maintien des temples et des statues des divinités dans le patrimoine et l’espace public des cités sous l’empire chrétien

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Témoignages épigraphiques sur le maintien des temples et des statues des divinités dans le patrimoine et l’espace public des cités sous l’empire chrétien show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Témoignages épigraphiques sur le maintien des temples et des statues des divinités dans le patrimoine et l’espace public des cités sous l’empire chrétienBy: Claude LepelleyAbstractThis article is a follow-up to the one published by the author in 1994 under the title “Le musée des statues divines”. A few documents that had not been used then, along with literary texts, laws and inscriptions, make it now possible to clarify some points, for example the ambiguity of the legislation that states the conservation of the pagan artistic heritage and at times supports destructions and re-uses. Conversely, several epigraphical evidences, from Rome, Italy or Africa, show above all the scale of operations of transfer or restoration of statues, as sometimes the result of intentional or accidental destruction. Whereas these statues had lost their religious character, their artistic value appeared as an inescapable element of adornment and urban heritage, in Rome as well as in the cities of the Empire. The importance of the epigraphic dossier shows both that legislation prohibiting destruction of buildings and works of art was actually implemented, and that the civic ideal inherited from early Roman Empire lasted all the same for several centuries.

-

Volumes & issues

-

Volume 32 (2024)

-

Volume 31 (2024)

-

Volume 30 (2022)

-

Volume 29 (2022)

-

Volume 28 (2021)

-

Volume 27 (2020)

-

Volume 26 (2019)

-

Volume 25 (2018)

-

Volume 24 (2017)

-

Volume 23 (2016)

-

Volume 22 (2015)

-

Volume 21 (2013)

-

Volume 20 (2013)

-

Volume 19 (2012)

-

Volume 18 (2011)

-

Volume 17 (2010)

-

Volume 16 (2009)

-

Volume 15 (2008)

-

Volume 14 (2007)

-

Volume 13 (2006)

-

Volume 12 (2005)

-

Volume 11 (2004)

-

Volume 10 (2003)

-

Volume 9 (2002)

-

Volume 8 (2001)

-

Volume 7 (2000)

-

Volume 6 (1999)

-

Volume 5 (1998)

-

Volume 4 (1997)

-

Volume 3 (1995)

-

Volume 2 (1994)

-

Volume 1 (1993)

Most Read This Month