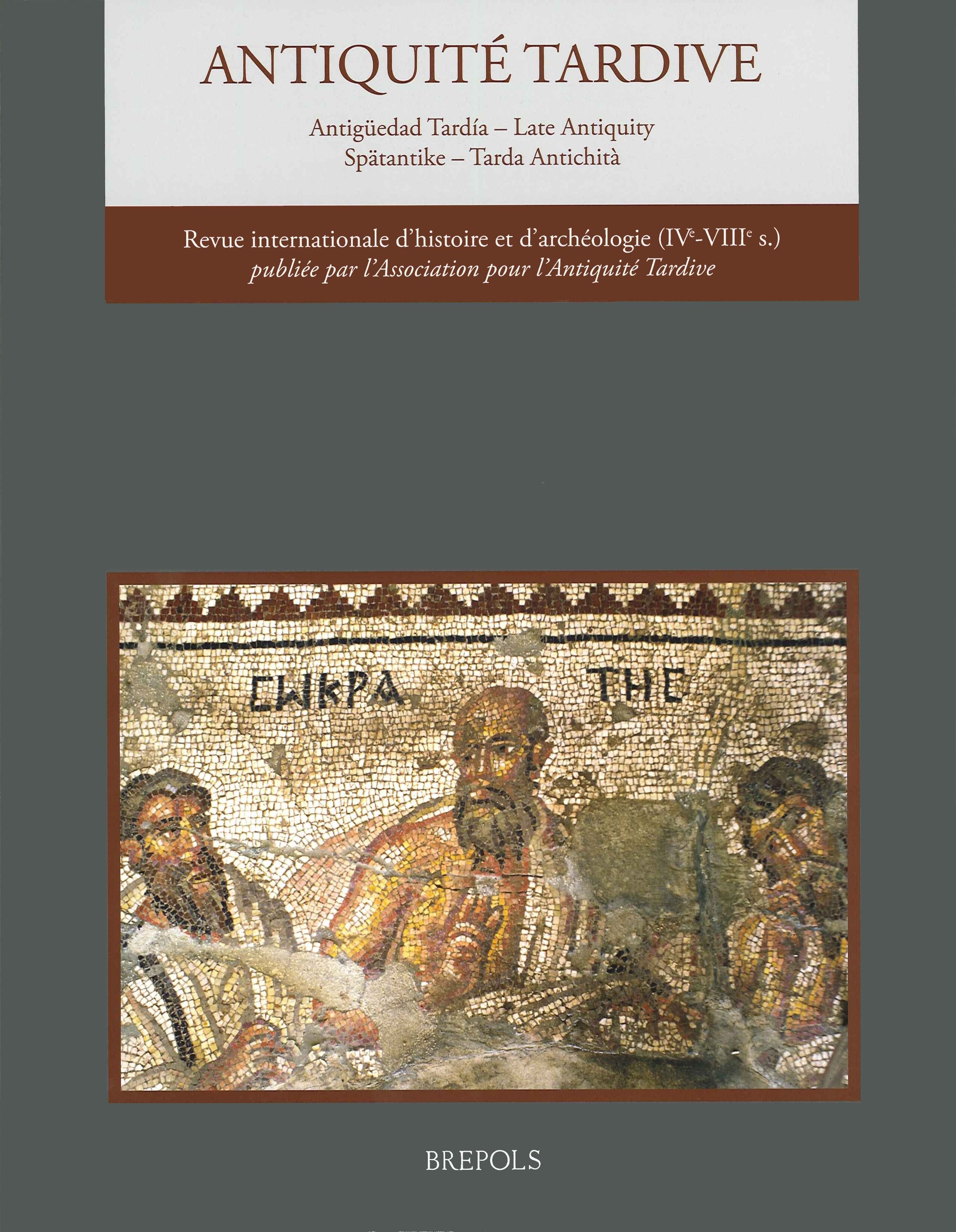

Antiquité Tardive - Late Antiquity - Spätantike - Tarda Antichità

Revue Internationale d'Histoire et d'Archéologie (IVe-VIIIe siècle)

Volume 21, Issue 1, 2013

-

-

Front Matter ("Comité de rédaction", "Page de titre", "Principales abréviations", "Table des matières", "Volumes parus", "Éditorial")

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Front Matter ("Comité de rédaction", "Page de titre", "Principales abréviations", "Table des matières", "Volumes parus", "Éditorial") show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Front Matter ("Comité de rédaction", "Page de titre", "Principales abréviations", "Table des matières", "Volumes parus", "Éditorial")

-

-

-

Naming rural structures from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages: the graeco-latin lexical resources and their modern uses (Part 2)

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Naming rural structures from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages: the graeco-latin lexical resources and their modern uses (Part 2) show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Naming rural structures from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages: the graeco-latin lexical resources and their modern uses (Part 2)AbstractThe way in which historians and archaeologists specialised in the study of the higher Middle Ages most frequently interpretet and use the graeco-Roman lexicon of earlier centuries makes it necessary to enlarge that of the 6th to 12th centuries given in the terminological enquiry presented in the first part of the curent issue: either to check how valid may be the meaning which they assign to terms inherited from Antiquity or try to situate the semantic discontinuities which occurred in the continuative use of Latin in the western world or Greek in the eastern one. With this view in mind we shall tackle successively such problems as the semantic itinerary of the word villa, of the lexical pairs castellum / castrum, villa-village, vicus and village, kômè-chorion, of the trio castellum / castrum / village, etc. When doing this, we shall take into account the great diversity in the local situations, the unequal rythm of transformation among the various language levels - learned or familiar, juridical or historiographical, etc. -, and the frequently met with difficulty of equating the language of the texts with the archaeological structures. On the other hand, we shall try to evaluate how much the meaning assigned by modern scientists to such or such resilient Latin word could determine the choice in favour of such or such theoretical model, with special regard to “villa to village” or “incastellamento” models. This will allow, more generally, the acknowledgement of the current state of archaeological reflexion regarding rural structures and how adequate the terminology used may be to field data. Our conclusions are mainly concerned with the interpretation of the words villa and castrum when found in the higher medieval sources.

-

-

-

Northern Britain in Late Antiquity

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Northern Britain in Late Antiquity show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Northern Britain in Late AntiquityAbstractLes sources littéraires et les données archéologiques concernant les régions situées au nord du Mur d’Hadrien, dans les îles Britanniques nous donnent une image assez contrastée des iiie-ve siècles de notre ère. D’après les textes, le iiie siècle apparaît comme une période paisible sur la frontière septentrionale. En revanche, le ive siècle est marqué par des incursions et des invasions, notamment de la part des Pictes, souvent décrits sous les traits stéréotypés de barbares. La documentation archéologique de son côté montre des habitats assez modestes à bâtiments circulaires dotés de peu de mobilier. L’archéologie funéraire reste également assez simple. Seules quelques fortifications de hauteur - hillforts - donnent l’impression d’une société plus complexe ; le site de Traprain Law notamment nous a livré le célèbre trésor de Hacksilber daté du milieu du ve siècle. L’archéologie du sud du Mur se différencie peu de celle du nord et paraît montrer, pour la fin du ive siècle, un affaiblissement de l’influence romaine dans la moitié nord du diocèse des Britanniae. Puis, la « chute » du pouvoir impérial semble avoir provoqué des changements importants dans l’Écosse actuelle, conduisant vers les royaumes du haut Moyen Âge.

-

-

-

Rural settlements in the middle Danube region from Late Antiquity to Middle Ages

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Rural settlements in the middle Danube region from Late Antiquity to Middle Ages show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Rural settlements in the middle Danube region from Late Antiquity to Middle AgesBy: Alois StuppnerAbstractThe most typical settlements in the middle Danube region during the Migration Period were those located on hilltops, on fluvial terraces or atop small elevations alongside rivers and streams. Compared to the preceding Roman period the area was less densely populated. The most characteristic element of the region’s settlements was the pit-house, now with a new, slightly changed post arrangement. A fireplace found in one of the pit-houses proves that they were not used as workshops alone, but also as dwellings. The concurrent existence of Migration Period and Roman-type pit-houses reflects the continuous settlement of the region since the Roman period.

During the 5th century AD different groups of settlements can be defined in the middle Danube region. The settlements in the area around Oberleiserberg, for example, are characterized by houses with Romanized architecture and furnishings. Another settlement group is restricted to the left bank of the Danube, usually near bridgeheads. Late Antique-type pottery was produced in these settlements, probably to supply the inhabitants of Roman cities and settlements along the Danube limes, as well the market north of the Danube. From the end of the 4th century AD onwards features and pottery complexes typical of non-Roman settlements appear in settlements of the Roman Provinces, evidence perhaps for different groups of Suebic or Herulic settlers, or Romanized settlers from beyond the Danube River.

The emergence of hilltop settlements is another very typical feature of the middle Danube region during the first half of the 5th century AD. Hilltop sites of this period are usually interpreted either as central seats of local holders of power, military strongpoints, or as places of refuge for the local population. The hilltop settlement at Oberleiserberg near Ernstbrunn appears to have been a late-Suebian stronghold of the 4th and 5th century AD. The Oberleiserberg pottery finds and features reflect a strong Roman influence. Roman military and other Roman-style architecture, together with Late Antique upper-class villas served as models for the construction of the principal, most substantial building and the adjoining houses.

-

-

-

Goths on the lower Danube: their impact upon and behind the frontier

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Goths on the lower Danube: their impact upon and behind the frontier show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Goths on the lower Danube: their impact upon and behind the frontierBy: Andrew PoulterAbstractCet article traite d’un certain nombre d’aspects relatifs à l’installation des Goths dans le Bas Danube. Il ne semble pas que l’accord de 382 ait eu l’impact supposé jusqu’à maintenant. Bien qu’il soit admis, grâce au bas-relief de la colonne d’Arcadius, que les populations indigènes reconnaissaient les Goths par leurs vêtements et, bien entendu, par leur langue, rien dans la documentation archéologique ne permet de distinguer ces derniers des « natifs ». Par ailleurs, la culture de « Săntana-de-Mureş / Cherineakov » ne paraît pas avoir existé : le seul élément trouvé dans les installations attribuées à cette « culture » (et aux Goths) est en réalité d’origine romaine et il n’y a aucune preuve que les autres éléments soient « gothiques ». Enfin, à la lumière des témoins archéologiques concernant la période suivant la bataille d’Andrinople et la première moitié du ve siècle, il apparaît que, quelle qu’ait été l’origine ethnique des occupants, une nouvelle politique a été engagée vers 400, qui a entraîné la construction de nouveaux forts et le réaménagement de plus anciens de manière à accueillir des soldats-fermiers. Malgré la disparition du système économique des villas, l’exploitation agricole a continué jusqu’à l’arrivée des Huns. Durant cette période (400-445), l’autorité militaire romaine et l’impôt de l’annone ont joué un rôle capital dans la préservation de la paix et les garnisons de soldats, qui étaient également engagées dans l’agriculture, ont assuré la sécurité sur la frontière comme à l’intérieur des terres, en même temps qu’elles ont continué à exploiter la richesse des ressources agricoles.

-

-

-

Structures of the rural settlement of the Venetian area and Emilia Romagna between the 4th and 9th centuries

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Structures of the rural settlement of the Venetian area and Emilia Romagna between the 4th and 9th centuries show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Structures of the rural settlement of the Venetian area and Emilia Romagna between the 4th and 9th centuriesBy: Claudio NegrelliAbstractThe study is devoted to the structures of coastal and rural populations of the large territory of the Venetian area and Emilia Romagna between the 4th and the 8th/9th centuries. The first reviewed data derive from research projects based on surveys: the Late Roman settlement pattern, despite evidence for a general decline of the sites, shows a reorganization of land holdings with different outcomes in different territories. A comparison with the data from excavations provides evidence for simple structures built over the villas or wooden huts with no ties to the previous structures of the Roman period. The early Middle Ages are marked by a trend towards centralization (villages, curtes central places, castles, etc..) together with a scattered settlement which was highly mobile and difficult to document, which in some areas continues to be based on previous fundia. The most economically vibrant structures are located along the Adriatic coast. A series of Late Antique settlements comprises functions related to roads, navigation, and handicraft production. In some cases urban sites were created ex novo.

-

-

-

L’habitat rural dans la péninsule Ibérique entre la fin du ive et le début du viiie siècle : un essai interprétatif

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:L’habitat rural dans la péninsule Ibérique entre la fin du ive et le début du viiie siècle : un essai interprétatif show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: L’habitat rural dans la péninsule Ibérique entre la fin du ive et le début du viiie siècle : un essai interprétatifBy: Enrique AriñoAbstractLa documentation archéologique concernant l’habitat rural de la péninsule Ibérique de la fin du ive au début du viiie siècle s’est largement développée ces dernières années. Or, le corpus d’information résultant des interventions archéologiques s’avère très complexe, de sorte que sa classification et sa systématisation exigent l’analyse détaillée de chaque cas documenté. L’étude individuelle des sites permet d’observer que, dans l’ensemble des hameaux paysans non fortifiés composés d’habitations et d’installations agricoles, il existe des différences qui se manifestent dans l´entité, la morphologie et les lignes évolutives présentes au long de la séquence. De la même manière, les sites fortifiés - qui constituent un phénomène propre et caractéristique de l’habitat rural de la période analysée - ne constituent pas non plus un groupe homogène. Dans ce groupe, il convient de différencier les sites fortifiés de création nouvelle - qui présentent des structures d’habitation et des contextes archéologiques très similaires - d’autres sites fortifiés qui sembleraient répondre à diverses circonstances, et notamment à des fonctions stratégiques. Le phénomène de la réoccupation des agglomérations fortifiées préromaines ou romaines (castros) devient extrêmement complexe et doit être défini avec plus de précision dans la mesure où il paraît répondre à des situations très diverses. L’analyse de la documentation montre que l’étude de l’habitat rural ne peut être dissociée de l’étude des nécropoles et des bâtiments religieux et qu’elle doit être associée à la structure de la propriété. Bien que le matériel archéologique recueilli sur les sites ne permette pas en général d’établir de précisions chronologiques, l’étude de l’occupation de l’habitat doit s’attacher à distinguer les phases afin de détecter les changements du mode d’occupation rurale sur une période qui s’étend sur plus de trois siècles.

-

-

-

Settlements in the Greek countryside from 4th to 9th century: forms and patterns

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Settlements in the Greek countryside from 4th to 9th century: forms and patterns show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Settlements in the Greek countryside from 4th to 9th century: forms and patternsBy: Myrto VeikouAbstractL’habitat rural en Grèce du ive au ixe siècle présente des aspects déjà assez bien connus, comme les villae et les villages, mais également d’autres formes qui ne sont pas encore clairement identifiés, leurs traits caractéristiques n’étant pas assez bien décrits ni précisément définis. Cet article aborde tous les types d’agglomérations dont les habitants participent à des activités économiques de nature rurale. À côté des implantations classiques, quelques nouvelles formes sont ainsi identifiées. On prend aussi en compte des changements de structure et de rôle de ces agglomérations, observables dans l’ensemble de l’habitat rural de la Méditerranée orientale, tout en y distinguant deux sous-périodes : du ive siècle à la première moitié du vie environ, et de la deuxième moitié du vie siècle jusqu’au ixe.

-

-

-

Rural dwellings of northern Syria (4th-6th centuries – ğebel Zāwiye, village of Serğilla)

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Rural dwellings of northern Syria (4th-6th centuries – ğebel Zāwiye, village of Serğilla) show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Rural dwellings of northern Syria (4th-6th centuries – ğebel Zāwiye, village of Serğilla)Authors: Catherine Duvette, Gérard Charpentier and Claudine PiatonAbstractThe Limestone Massif of northern Syria constitute an extraordinary group of archaeological settlements. They include over 700 sites from the Roman and Byzantine periods in a wide region bordered by Turkey in the north, Apamea in the south, the Afrin and Oronte’s valleys in the west and the plain of Aleppo in the east. These sites are not only important for their profusion, but also for their rural nature. The recent and detailed study of the well preserved remains of one of these settlements, Serğilla, located in the ğebel Zāwiye, offered the opportunity to explore various aspects of the daily life of a rural community and its evolution between the 4th and the 6th centuries AD. Three houses among others, built during different phases of the development of the village, are emblematic of this evolution.

-

-

-

Identifying social hierarchy through house planning in the villages of Late Antique Palestine: the case of Ḥorvat Zikhrin

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Identifying social hierarchy through house planning in the villages of Late Antique Palestine: the case of Ḥorvat Zikhrin show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Identifying social hierarchy through house planning in the villages of Late Antique Palestine: the case of Ḥorvat ZikhrinBy: Itamar TaxelAbstractL’article aborde la délicate question de l’identification du statut juridique et social des habitants d’établissements ruraux de la Palestine tardo-antique documentés par l’archéologie. Il s’appuie pour cela notamment sur les données architecturales recueillies lors de la fouille d’un site villageois très représentatif du centre de l’actuel état d’Israel, Ḥorvat Zikhrin. Si l’agencement des habitations durant l’Antiquité tardive y est similaire à celui d’autres villages palestiniens contemporains, on y relève aussi certaines caractéristiques bien spécifiques qui incitent d’autant plus à tenter de restituer la structurtation sociale du site.

-

-

-

Fortified farms and defended villages of Late Roman and Late Antique Africa

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Fortified farms and defended villages of Late Roman and Late Antique Africa show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Fortified farms and defended villages of Late Roman and Late Antique AfricaAuthors: David Mattingly, Martin Sterry and Victoria LeitchAbstractLes fermes et autres sites fortifiés ont marqué les paysages de l’Afrique du Nord au cours de l’Antiquité Tardive. Leur présence y a été relevée dans toutes les provinces romaines, y compris dans les zones situées au-delà des frontières, comme le coeur de la contrée des Garamantes dans le Fezzan (sud-ouest de la Libye). Huit types de fortifications sont ici définis afin de servir de base à un réexamen de la répartition des fortifications rurales publiées à la suite des principales prospections archéologiques conduites dans ces régions. On constate de nettes prédominances régionales, tels que les villages fortifiés en Numidie, les temples et mausolées convertis en maisons carrées dans la steppe tunisienne et les églises fortifiées en Cyrénaïque. Toutefois, dans presque toutes les régions, les sites fortifiés jouent un rôle essentiel dans la hiérarchie des établissements. En Tripolitaine et au Fezzan, par exemple, ces sites fortifiés sont majoritaires. Les constructions le plus précoces sont datées du iie siècle après J. C. et leur occupation a continué jusqu’à l’époque islamique, mais, en Libye au moins, la majorité des constructions se situent au cours du ive siècle. Bien que certains sites fortifiés s’inspirent de modèles militaires, on soutient l’hypothèse que, loin d’être stimulé par l’armée romaine, ce phénomène de protection doit être interprété dans un contexte de faiblesse de l’autorité centrale et d’essor de l’indépendance régionale.

-

-

-

Ecclesiastical foundations in rural areas: some remarks about the Late Antique West (4th-5th centuries)

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Ecclesiastical foundations in rural areas: some remarks about the Late Antique West (4th-5th centuries) show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Ecclesiastical foundations in rural areas: some remarks about the Late Antique West (4th-5th centuries)AbstractThe problem of the christianization of the countryside has been examined since the 18th century, mainly from the institutional point of view; the question was the origin of the organization of the Medieval parish, whose territorial structure was compared with the roman pagus system. In the last few decades a more critical appraisal of the written sources, new approaches to the spatial issues and archaeological discoveries have led to a different perspective, focused not only on the continuity but also on the transformations which took place between Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. This paper considers the very beginning of this process; by taking into account both written and archaeological sources it shows that in the 4th-5th centuries there is no evidence of a real programme of christianization of the countryside. The construction of cult buildings which mark the spread of Christianity is due in turn to the personal initiative of landowners, bishops and communities. Their localisation therefore, while corresponding to the different types of settlements in Late Antiquity, do not follow an evident, systematic pattern.

-

-

-

Church and settlement in southern France in the 5th to 10th centuries

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Church and settlement in southern France in the 5th to 10th centuries show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Church and settlement in southern France in the 5th to 10th centuriesBy: Yann CodouAbstractLinks between church and settlement in the south of France have lead up to many considerations in view of the centuries immediately following the field of our study. During the 5th-10th centuries, places of worship and housing were closely related to each other, even if they sometimes did not have any straight spatial connection. According to various archaeological sources, it is clear that the setting up of a place of worship was associated with a settlement and even reinforced it; on the other hand, settlement was affected by both stability and mutation in comparison with the former centuries. As the topic of rural communities has been widely studied these last years, it seems important today to reconsider the place of private churches over a large time scale. The question is furthermore linked to that of cemeteries. Even if only partially complete, the evidence for trends during the 5th-10th centuries will certainly change our view of the 11th-12th centuries for which the importance of their legacy is far from being secondary.

-

-

-

Christians, peasants and shepherds: the transformation of the countryside in Late Antique Mallorca (Balearic islands)

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Christians, peasants and shepherds: the transformation of the countryside in Late Antique Mallorca (Balearic islands) show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Christians, peasants and shepherds: the transformation of the countryside in Late Antique Mallorca (Balearic islands)Authors: Catalina Mas Florit and Miguel Ángel CauAbstractCet article propose une synthèse sur la dynamique du processus de transformation des campagnes dans l’île de Majorque entre la période romaine et la fin de l’Antiquité tardive. Y sont envisagés le phénomène de la réoccupation d’anciens emplacements indigènes, le sort des sites ruraux romains et le rôle des églises chrétiennes - autant de paramètres essentiels pour bien appréhender la configuration du paysage de cette île méditerranéenne entre le ive et le viiie siècle. Les témoignages disponibles montrent qu’à la fin du iie ou au début du iiie siècle, un grand nombre d’emplacements avaient été abandonnés ; cela s’est « inversé » dans la seconde moitié du ve siècle et particulièrement au vie siècle, avec la réoccupation d’une grande partie des sites romains ; parallèlement, de nouveaux signes d’activité sont alors attestés sur de nombreux sites préhistoriques.

-

-

-

City and countryside in Late Antique Iberia

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:City and countryside in Late Antique Iberia show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: City and countryside in Late Antique IberiaBy: Damián FernándezAbstractDepuis une vingtaine d’année, l’historiographie de la péninsule Ibérique envisage de plus en plus fortement la continuité des relations entre ville et campagne du iiie au vie siècle, en dépit d’importantes mutations des cultures matérielles. En l’absence de documents écrits, les détails de ces relations et de leurs éventuelles transformations nous échappent, mais l’archéologie a ouvert de nouvelles voies d’investigations qui ont permis de les envisager sous un angle différent. L’article examine ici l’interaction ville / campagne sous trois axes : culturel, politique et économique. Pour chacun de ces axes, un état actuel de la recherche est présenté en parallèle d’une brève discussion sur les possibilités et les limites des nouveaux témoignages archéologiques. De manière générale, ces nouvelles approches amènent à une façon originale et créative de concilier la permanence des relations cité / territoire avec les importants changements dont témoignent les données archéologiques.

-

-

-

Rural areas and urban centres from 4th to 7th centuries: the case of Tuscany

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Rural areas and urban centres from 4th to 7th centuries: the case of Tuscany show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Rural areas and urban centres from 4th to 7th centuries: the case of TuscanyBy: Federico CantiniAbstractIn this paper the relationship between rural and urban areas from the 4th to 7th centuries is discussed. We shall explore its changes first in general terms (mostly in central and northern Italy), and then in the Tuscany. Archaeological evidence highlights the different dynamics acting on North and South. A complex picture emerges, where the role and the fate of the city and its aristocracy are crucial for the interpretation of observed transformations of the rural areas.

The need to supply urban centres, demographic trends, the transformation of the Mediterranean economy and tax system, combined with political and military events, defined new forms of relationship between the cities and the countryside, particularly from the end of the 6th-7th centuries.

By this time the Roman institutional and fiscal links between the city and the countryside were largely replaced by the aristocratic network of land ownership. Villas, often monumentalised in the 4th century (especially in the north of the region), and farms were replaced by villages and a few central places directly linked to the cities, where the new aristocracy also continued to live.

-

-

-

Aleae aut tesserae? The meanings of gaming opponents in the Rome of Ammianus Marcellinus

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Aleae aut tesserae? The meanings of gaming opponents in the Rome of Ammianus Marcellinus show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Aleae aut tesserae? The meanings of gaming opponents in the Rome of Ammianus MarcellinusAbstractMany ancient writers have left testimonies about the social significance of Roman leisure. Rather than trying to draw an artificial presentation of the tabula lusoria of Late Antiquity, this paper considers the meaning of an Ammianus Marcellinus’ description of the Roman attraction for the alea. The focus here is on the board games played at Rome at the end of Late Antiquity in order to better understand the text. A first step is to analyze relations between urban society, aristocratic values and gaming practice. A second step consists in clarifying the gaming vocabulary of alea and more precisely the use of the word tessera. The guiding hypothesis is that tessera does not mean just “dice” but also “pawn”, and more generally the instrumentum of the gaming board.

As a result, I suggest that Ammianus was not just a malicious observer but a very fine satirist who turned the aristocratic discourse against the nobilitas of Rome.

-

-

-

The transformation of hostageship in Late Antiquity

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:The transformation of hostageship in Late Antiquity show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: The transformation of hostageship in Late AntiquityBy: Adam J. KostoAbstractLa présente étude propose un bilan sur l’institution de l’otage (le transfert d’un être humain en garantie d’une transaction) dans l’Antiquité tardive, fondé sur l’analyse de près de 140 cas entre le ive et le viiie siècle, des îles Britanniques à l’Asie centrale. Dans l’Antiquité, l’otage constituait avant tout un signe et un symbole de soumission, mais aussi un vecteur de « diplomatie culturelle », et était presque toujours livré à Rome. Alors que son pouvoir diminuait par rapport à ses voisins, Rome continuait à échanger des otages dans des circonstances très variées : non seulement de traités « internationaux », mais aussi d’accords à court terme pendant la guerre ou encore pour régler les relations intérieures. L’otage cesse alors d’être une prérogative de l’empereur même. Dans l’empire byzantin et l’empire islamique primitif, se développe un modèle d’otage particulier : il est donné, reçu et échangé par des personnes ou des groupes variés, dans le cadre d’accords limités ou de soumissions à durée indéterminée, en relation avec des affaires internes ou externes aux régimes.

-

-

-

Hired labourers on Late Antique estates

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Hired labourers on Late Antique estates show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Hired labourers on Late Antique estatesBy: Christel FreuAbstractDuring the last decade, interesting perspectives have been developed regarding the rural labour force in Late Antiquity. Notably, Jairus Banaji, in his book Agrarian Change in Late Antiquity. Gold, Labour, and Aristocratic Dominance (Oxford, 2001), insisted upon the importance of salaried people on late Antiquity estates. This article provides additional information on this type of employment, comparing law, papyri and texts. While the legal setting indicates that the labour contract was one type of employment on estates, other sources underscore the limited importance of salaried workers, who were principally employed for a limited number of specific tasks: tending cattle; in specialized agriculture such as viticulture; and on irrigation works. It does not appear that the majority of tenants on these estates were in fact wage earners.

-

-

-

Provincia Lucania: topography and land survey in a changing landscape, from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages (part 1)

show More to view fulltext, buy and share links for:Provincia Lucania: topography and land survey in a changing landscape, from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages (part 1) show Less to hide fulltext, buy and share links for: Provincia Lucania: topography and land survey in a changing landscape, from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages (part 1)AbstractProvincia Lucania is the name used by sources in Late Antiquity to define the part of ancient regio III which the Diocletianic reforms included as one of the most productive regions of suburbicarian Italy. The heterogeneity of the studies carried out in the past and the treatment of archaeological and philological data together with statistical examples, even extended to non investigated parts, underestimate the exact content of textual, epigraphic and mapping sources about this land as well as the connections which existed between distant but culturally very close localities. The topographic analysis of the provincia also take place together with the surveyors’ texts, in such a way that the evolution of the landscape from the 5th to the 11th centuries emerges by comparing and relating the latter to the reality. The different versions of Tabula Peutingeriana, the itineraria and the so-called Liber Coloniarum or Regionum are here decoded and open up new perspectives to analyze a still largely unknown territory.

-

Volumes & issues

-

Volume 32 (2024)

-

Volume 31 (2024)

-

Volume 30 (2022)

-

Volume 29 (2022)

-

Volume 28 (2021)

-

Volume 27 (2020)

-

Volume 26 (2019)

-

Volume 25 (2018)

-

Volume 24 (2017)

-

Volume 23 (2016)

-

Volume 22 (2015)

-

Volume 21 (2013)

-

Volume 20 (2013)

-

Volume 19 (2012)

-

Volume 18 (2011)

-

Volume 17 (2010)

-

Volume 16 (2009)

-

Volume 15 (2008)

-

Volume 14 (2007)

-

Volume 13 (2006)

-

Volume 12 (2005)

-

Volume 11 (2004)

-

Volume 10 (2003)

-

Volume 9 (2002)

-

Volume 8 (2001)

-

Volume 7 (2000)

-

Volume 6 (1999)

-

Volume 5 (1998)

-

Volume 4 (1997)

-

Volume 3 (1995)

-

Volume 2 (1994)

-

Volume 1 (1993)

Most Read This Month